|

|

![]()

| Krantz Sydney Major SX13978 |

| Medical Officer 13 Australia General Hospital (AGH) and 2/4 Casualty Clearing Station (CCS) |

Sydney Krantz was born in Adelaide on 24 September 1903. He studied medicine at Adelaide University and graduated in 1927. This was followed by postgraduate study in England where he became a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons (FRCS) in 1931 and a Fellow of the Royal Australian College of Surgeons (FRACS) in 1938. He enlisted in the AIF on 7 August 1941 and was commissioned as a Major in the 13th Australian General Hospital (AGH).

The 13 AGH was moved to Singapore/Malaya on the HMAHS Wanganella in September 1941 and along with 10 AGH provided hospital cover during the battle for Malaya and Singapore. Initial deployment was to the Malayan mainland at Johore Bahru.

It seems that Major Sydney Krantz was attached to 2/4 Casualty Clearing Station(CCS) some time in December 1941. This move was probably to boost the surgical capacity of that unit and he formed part of a Mobile Surgical Team. This team comprised Sydney Krantz, Capt Tom Brereton and 6 medical orderlies and they had 2 vehicles. He became one of three surgeons in the CCS (the others being the Commanding Officer Lt Col Thomas Hamilton and Sydney’s friend and pre war college from Adelaide, Major Alan Hobbs). It is worth noting a comment in “The story of the 13 Australian General Hospital” written by Lex Arthurson, where he comments “Major Krantz was thus lost to us. The man, a brilliant surgeon, could, in the words of some, “Cut my head off and sew it on again”. All medical personnel - medical officers, nurses (female remaining at that stage) and medical orderlies performed with distinction.

Following are two extracts from Lt Col Thomas Hamilton’s book “Soldier Surgeon in Malaya” which, whilst relating to Major Syd Krantz, are indicative of what the unit was going through. From page 43-

“Major Syd Krantz came in at that moment, so I went with him to his surgical ward to see the Air Force patient he had operated on three days previously. An unfortunate flight-sergeant had walked into a whirling propeller at Kluang aerodrome. The prop laid his left shoulder open like a side of raw beef. Brought to our resuscitation room shocked and exhausted from loss of blood, he had needed a large transfusion to revive him sufficiently to make an operation possible. When we looked at him later in the theatre, it seemed as though his arm must be amputated.

Syd Krantz, gowned, masked and gloved, was standing ready while his surgical team carefully cleansed the large, gaping wound. As we watched, a pulsation was noticeable in the depths of the wound. Syd’s skilful hands gently separated the torn muscles, revealing the main artery and vein of the arm intact. I saw his face relax under the mask and knew, as he did, that the arm had a chance. Our eyes turned to Major Hobbs, looking on from the foot of the table. Syd grunted. “I think we’ll give it a go!”

Alan Hobbs agreed. The torn limb was sutured gently into position, the wound drained with a tuule gras dressing and the arm bandaged to the chest. Then Sister Kinsella (who perished when the Vyner Brook was sunk of 14 February 1942) took charge……….and applied her splendid nursing technique to the task of nourishing the small spark of life left in the patient……His arm was saved.”

From page 70, being an extract from the 2/4 CCS War Diary-

“15 January 1942. At 1800 hours a convoy arrived with 36 casualties, and from this time more arrived steadily. During the period 1800 hours to 0600 on 16th, 165 cases were admitted and 35 operations were carried out by Majors AF Hobbs and S Krantz. The CO took over in the morning and completed the remaining cases in order to give the other surgeons a rest. 73 cases were evacuated by the 2/3 MAC at 0600 hours…..”

It is unfortunate that Lt Col Hamilton did not write about the medical experiences of the 2/4 CCS on the Burma end of the Burma Thailand Railway. Fortunately Capt Rowley Richards authored two books- “The Survival Factor” ISBN 0 86417 246 X and in 2005 “A Doctor’s War” ISBN 0 7322 8009 5 & 9780 7322 8009 3. Both books are excellent and give a description of the work of a junior medical officer operating, basically on his own (as part of Anderson Force) with little prospect of support from fellow professional colleagues. Rowley’s book also includes his experiences when torpedoed en route to Japan and his subsequent time in Japan).

I have been fortunate in being given copies of four addresses which Syd Krantz made to medical colleagues post war. The dates of the addresses are not known. Only one of the addresses has been typed in full. Additional information which was included in the other three addresses has been added as additional notes.

AN ADDRESS TO PROFESSIONAL COLLEAGUES BY MAJOR (Dr) SYDNEY KRANTZ MEDICAL OFFICER 2/4 CASUALTY CLEARING STATION 1941 - 1945

Mr. Chairman, Mr. Vice President, Fellows and Gentlemen.

I am very pleased to see my former POW colleague Alan Hobbs here.

I would like to thank the Committee for inviting me to talk on this subject this morning. Actually this is my second invitation – the first being 26 or 27 years ago when I think the late Sir Ivan Jose was chairman and who later, of course, became President of the College.

Just to remind you of the era about which I will be referring to – England declared war on Germany in 1939. This was followed soon after by Australia’s Declaration. The Japanese sank the major part of America’s Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbour in Dec. 1941 and a little later sank the British Warships Prince of Wales and Repulse off the coast of Malaya. They then began their conquest of Malaya, Singapore and the Dutch East Indies, as this territory was called in the Pre-Sukarno days.

The British and Indian troops were pushed down the Malayan Peninsula to a place called Gemas and it was at this point that the AIF troops first came into action. The 2/4 Casualty Clearing Station, housed in large tents and with good x-ray equipment, was situated in a rubber plantation at Kluang. We were all set to receive the Australian casualties. Alan Hobbs and myself, as the two surgeons to the unit, had plenty to do in these days.

I will not have time this morning to talk about the surgical aspects of the Malayan Campaign, which ended after the retreat to Singapore Island and the ultimate surrender of 96,000 men in Feb 1942 including the loss of almost the whole of the small Air Force, but more important, as far as Australia was concerned, the destruction of the mighty Singapore Naval Base.

We did not hear until much later about the loss of many of our Army Nursing Sisters who were evacuated too late. You have probably read of the Banka Straits tragedy resulting in Sister Bullwinkel as the only survivor. The next stage was the incarceration of the civilian prisoners into Changi Gaol. Most of the troops, battle casualties and medical units were herded into Changi Army Barracks. We were permitted to carry on with our surgical work – mainly dealing with highly suppurating wounds. We had Sulphanilamide but not penicillin. Some of the men went down to 4-1/2 stone due to loss of protein in the pus, plus the lack of nourishment. Within 3 months, we began to see cases of cardiac beri-beri and arebinoflavinosis.

After about 3 months the Casualty Clearing Station and its equipment and 3,000 troops were herded into Japanese Merchant ships and moved to south Burma. Many others were shifted to work in Borneo and to the mines in Japan. Others spent the rest of their time in Changi, working in Singapore.

We steamed up the Straits of Malacca, which is a very important waterway today and picked up more Prisoners of War in Sumatra – including Lt Col. Coates – now Sir Albert and who became the Senior Surgeon at the Royal Melbourne Hospital and a well known Fellow of the College.

Conditions on these ships – you can well imagine, were indescribable. In south Burma the men worked on aerodromes and other military installations.

The first operation performed after leaving Changi was done by Lt Col (Sir) Albert.

We were then herded into more ships and moved to Moulmein where I slept on the concrete floor of the local gaol and from then on we began to build the Burma Thailand Railway which was to bridge the territory between Bangkok in Thailand to Rangoon in Burma and which, when built, was used to supply the Japanese army in its unsuccessful attempt to capture India. Many more Prisoners of War reinforcements were sent to the Burma end and a larger force to the Thailand end.

By the end of 1943 the two working forces had met and the Railway was finished.

The work was entirely done by physical man-power plus the use of a few elephants. I did not see any mechanical equipment at any stage.

60,000 British, Australian, American and Dutch POWs were involved and many thousand Indians, Malayans and indigenous people. By 1943 – 15,000 POWs had perished and many more were disabled in one way or another for life. How many Indians and Asiatics died – no one will ever know.

I will not have time to tell you about the innumerable diseases we encountered, because I want to talk about the surgery that was done and how it was achieved, but it should be mentioned that we were operating on men who were suffering from starvation and malnutrition and all the deficiency diseases resulting there from, also chronic malaria, amoebic and bacillary dysentery, infective hepatitis, tropical ulcer and skin diseases and many others, including outbreaks of cholera.

Some surgery was done in the camps along the line by Alan Hobbs, Coates and myself. Coates amputated many (130) gangrenous legs resulting from tropical ulcer using cocaine as a spinal anaesthetic given to him by one of the dentists. Lt Col. Dunlop – now Sir Edward and who also became Senior Surgeon at the Royal Melbourne Hospital did a lot of good surgical work in camps at the Siam end of the railway. The Japanese gave us very little in the way of medical supplies – the most important being quinine and small supplies of cholera vaccine. They also paid us a little money and we traded our watches and fountain pens with the villagers in order to augment our meager rations. Our main diet was rice, small peas and sweet potato and we could at times buy bananas, limes and duck eggs.

About 18 months before we were released in late 1945 Lt Col Coates and myself and Major Fisher – a Senior Physician from the Sydney Hospital, were sent by train to an area about 50 kilos west of Bangkok to a small town called Nakonpaton, where there is the tallest Buddha Pagoda in Thailand. A large hospital camp was constructed here in a very short time, comprising 50, 100 metre long bamboo and atap roofed huts (to accommodate 200 patients each). It also had the luxury of an operating theatre with a good wooden operating table and a cement floor. We were later joined by Dunlop and other specialists. Amongst them was Dr FRCS Capt. (Professor) Markowitz of Toronto (now deceased) whose book, on Experimental Surgery is in our own Medical Library, was of inestimable value to us. Before long we had 7-8 thousand sick men in the camp and a team of about 30 medical officers. We also had a Capt. Tom Marsden of the Institute of Medical Research from Kuala Lumpur and he managed to produce a microscope from somewhere.

Sketch of the Pagoda at Nakonpaton- Artist Fred Ransome Smith (ex British POW Lt Fred (Smudger) Smith – 5 Suffolks)

The Japanese, sensing defeat, allowed, for the first time into the camp, a consignment of American Red Cross supplies which included novocaine and with Chemists, Botanists, Scientists, Architects, Engineers, Rubber Planters and especially men from the Australian outback – there was very little that could not be improvised. We even managed to produce a musical orchestra. By the time the war finished we had done 800 major and minor operative procedures.

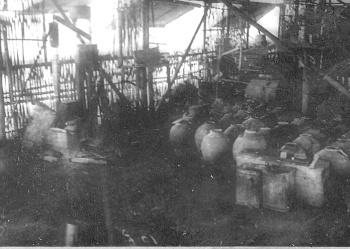

To do these operations we used spinal, epidural and local novocaine. We used cotton and unravelled silk sutures from parachute cords and we also made and sterilized our own catgut from animal intestines. Emergency operations at night were done by hurricane lamp, sometimes with a Japanese or Korean guard watching over us with a rifle on his shoulder. Some genius made a steam sterilizer and a foot operated suction machine. We had no gloves – but it did not seem to matter. Our diathermy was a long nail in red hot charcoal. Our only antiseptic apart from a little iodine was 90% alcohol made by the gallon out of rice. This I think was a tremendous achievement and really allowed us to do our work with reasonable asepsis. I can show you a slide of the still we used.

The powdered milk tins used as a baffle were soldered together using HCI sucked up by duodenal tubes as a flux. Someone made me a small serrated circular saw which we attached to a foot operated dental drill to cut a bone flap.

1,500 transfusions were done, Capt. Marsden matching the blood with his microscope and Capt. Markowitz using a bamboo brush to get the fibrin out and then draining the plasma through gauze. The classification of a donor in our camp was anyone who could stand up. Perhaps the most ingenious improvisation was the manufacture of artificial limbs with moveable knee, ankle and foot joints. We had 173 amputees in our camp – mostly the end result of gangrenous tropical ulcers, but in some cases due to bombs dropped on our camps by our own planes. I believe there were only three cases who could not be fitted because of stump troubles. We were very proud of this one:-

I think these two slides (only one shown above) should be kept in the War Memorial Museum Canberra to show what can be done by men whose morale was never at any stage shattered by the enemy in those days.

Then it all finished and Lady Mounbatten (since deceased) Chief of British Red Cross came in with two other women driving a jeep. This was a vehicle which we had never seen before. Her plane dropped supplies and clothing and the British Paratroopers then came in and sprayed us with DDT, which we also had never heard of.

Well I think this gives you a rough idea of what was done in those rather grim days. The essential requirements for our small success was a disciplined team effort

From other comments it clear that the above address was made post Vietnam War.

Separate matters which appeared in the other addresses follow-

- The Mobile Surgical Team treated compound factures and soft tissue injuries. He suspected that several were self inflicted.

One problem with treating fractures was that, in the humid climate, Plaster of Paris did not set. There was a need for much improvisation.

He treated British, Indian and Australian sick and wounded. - When in Burma, because of the shortage of medical supplies there was a need to ration what little supplies they had. He had a small amount of chloroform.

- The Medical Officer had to assess the fitness of the men to meet the Japs demands for working parties. If he did not provide the numbers demanded, he was bashed.

- Disorders encountered were- dysenteries, malaria, dengue, severe tropical ulcer, scabies, infected skin lesions, infective hepatitis, severe corneal abrasions, retroluber(?) neuritis and cholera.

- The Japs did supply some cholera vaccine and quinine.

- Dental cocaine was used as a spinal anaesthetic.

- In one period of 3 months was fed on nothing but rice and chillies.

- As the line progressed, the cruelty of the Jap officers and men in charge of the camps and the Korean guards became worse and the men were being bashed more and more. If one happened to be tall they made you kneel down so that they could hit you more easily.

- When the railway was finished and the POWs were moved to the hospital camp at Nakhom Pathom, Thailand.

- At the war’s end there were 173 amputees at the hospital camp at Nakhom Pathom, of which 3 had double amputations.

- One of the amputees had been enlisted without a leg. Some medical officer must have forgotten to tell him to take his trousers off. His artificial leg was used as a model for others to be manufactured at the hospital camp.

- At Nakhom Pathom he did 67 appendectomies.

- We held clinical meetings and conducted post mortems, but when the Japs found that they were being thrashed they stopped all these.

- Any good results were due to team work, especially from men who acted as medical orderlies and whose praises have been unsung and unrewarded,, especially those who attended the cholera cases.

- An interesting comments from Sydney Krantz’ notes follows-Adversity and segregation produce a closely knit community and the medical Officer has an important role to play, but I believe he has, to some extent, been over praised, because in my opinion it was the maintenance of strict discipline by our own working camp AIF and British senior officers, that was the greatest factor in keeping up the morale of the men, which no Japanese or Korean guard could ever conquer.

Article written by Lt Col Peter Winstanley OAM RFD JP. Email peterwinstanley@bigpond.com Website www.pows-of-japan.net .

I have been assisted by Mrs Kathleen Lancaster (Sydney Krantz widow) and his son Simon provided the hand written lecture notes and many slides. Reference to Thomas Hamilton’s book “Soldier Surgeon in Malaya” and Lex Arthurson’s book “The 13 Australian General Hospital” filled in many gaps. I thank my wife Helen for typing the hand written notes of Sydney Krantz.

Doctors have a reputation for poor hand writing. That should not apply to Sydney Krantz as his notes were quite legible.

The sketch of the Pagoda by Fred Ransome Smith (ex British POW Lt Fred (Smudger) Ransome Smith- 5 Suffolks), was drawn in 2005 from memory. Fred has two books of his sketches which can be obtained from him at 29 Seymour Grove, Brighton Beach, Victoria, Australian 3186 at a cost of $18 each, including postage, in Australia.

Note the variation of spelling of some of the names of some Thai locations. This was due to the corruptions that occurred due to the differences in pronunciation by Thai, Burmese and Japanese.

Sydney Krantz died on 11 August 1973. An obituary by his fellow POW and professional colleague Alan Hobbs can be viewed here:

Sydney Krantz Obituary by Alan Hobbs

|

|