|

|

![]()

| THE PERCIVAL REPORT |

| First published 1948 |

Events leading to the war

The following Despatch was submitted to the Secretary of State for War on April 25, 1946 by Lieut–Gen. A.E. Percival, C.B., DSO., O.B.E., M.C. formerly General Officer Commanding, Malaya.

It was officially released for publication by the War Office in London last night.

The Despatch says: -

The preparation of this Despatch on the Operations in Malaya which took place between December 8, 1941 and February 15, 1942, has been influenced by the fact that since the conclusion of those operations a great deal of literature has appeared on the subject.

Statements have been made and opinions expressed by writers, many of which have a cursory knowledge of Malayan conditions or of the factors which influenced decisions. Often these statements and opinions have been based on false or incomplete information.

The Malayan campaign had two novel features (a) It was the first large-scale campaign for a very long time to be fought within British or British-protected territory, and (b) It was our first experience of a campaign fought with modern weapons in jungle warfare conditions. In reading this Despatch it should be borne in mind that the knowledge which now exists was not at that time available to those responsible for the conduct of the operations, whose task it was in consequence to attempt to solve many new and novel problems.

General Remarks:

Malaya is a country where troops must be hard and acclimatized and where strict hygiene discipline must be observed if heavy casualties from exhaustion and sickness are to be avoided. The country generally tends to restrict the power of artillery and of Armoured Fighting Vehicles. It places a premium on the skill and endurance of infantry. As is true of most types of close country. It favours the attacker.

The form of government of Malaya was probably more complicated and less suited to war conditions than that of any other part of the British Empire. In pan-Malayan matters the High Commissioner could not deal with the four Federated States as one entity. He had to consult each, either direct or through the Federal Secretariat. More often than not he had to deal with ten separate bodies, i.e. the Colony plus the nine states, and sometimes with the Federal Government as well, making eleven. This naturally tended to cause delay when subjects affecting Malaya as a whole were under discussion.

The British Government had by various treaties promised to afford protection against external aggression to most, if not all, of these Malay States. This was a factor which had to be borne in mind in the conduct of the operations. In a country where there was so little national unity, it was natural that the Sultans should be inclined to consider the security of their own territory as of primary importance. Prior to the outbreak of World War 11 there was a Defence Organisation in Malay modelled on the committees of Imperial Defence at Home. There were a number of sub-committees. The members of these sub-committees were as a rule partly military and partly civil.

Up to November, 1940, the three Fighting Services worked independently, the commanders of the Army and Air Force being responsible direct to their own Ministries. The Senior Naval Officer at Singapore was originally responsible only for the sea defences of Singapore Island and for the local defence of the adjoining waters. Later he became, as Rear-Admiral, Malaya, responsible for all the coasts of Malaya.

From July 1940 onwards, however, the Naval Commander-in-Chief, China Station, flew his flag on shore at Singapore and assumed responsibility for all the waters off the coasts of Malaya, except that the responsibility for those off Singapore Island was still delegated by the Rear Admiral. In October 1940, a Commander-in-Chief Far East (C.I.C. Far East) was appointed, the position being filled by Air Chief Marshal Sir Robert Brooke-Popham.

He was informed that the two main principles to guide his actions were

(a) It was the Government’s policy to avoid war with Japan,

(b) Reliance for the defence of the Far East was to be placed on Air Power until the fleet was available.

He was further instructed that the General Officer Commanding (G.O.C.) Malaya was to continue to correspond with the War office on all matters on which he had hitherto dealt with it, to the fullest extent possible consistent with the exercise of his command.

The C-in-C Far East had no control over any naval forces, nor did he have any administrative responsibility, the various Commands continuing to deal with their respective Ministries in this respect. The C-in-C, Far East therefore, had only a small operational staff and no administrative staff.

Becomes G.O.C.

On May 18, 1941, I assumed the duties of G.O.C. Malaya Command. I had previously served as Chief of Staff Malaya Command (General Staff officer 1st Grade) in 1936 and 1937. At that time the Air Officer Commanding Far East was Air Vice-Marshal C.W. B. Pulford. He had taken over command only a short time previously.

The Commander-in-Chief China was Vice-Admiral Sir Geoffrey Layton. Rear-Admiral Drew was Rear Admiral Malaya but was shortly afterwards succeeded by Rear-Admiral Spooner. When hostilities started the headquarters of the Army, the Royal Air Force and the Civil Government were grouped in one area, while those of the two Commanders-in-Chief and of the Rear-Admiral Malaya were grouped in another some 10 miles or more apart. This was far from an ideal solution, but possibly the best under the circumstances.

Had there been at that time a Supreme Commander with an integrated staff probably many of these difficulties would have disappeared.

Staff Difficulties

With the increase in the garrison as the defences developed and relations with Japan became more strained, so there was an increase in the strength of Headquarters, Malaya Command. After the outbreak of war with Germany the filling of vacancies on the staff became more and more difficult as the supply of trained staff officers in the Far East became exhausted.

Regular units serving in Malaya were called upon to supply officers with qualifications for staff work until it became dangerous to weaken them any further and selected officers were sent for a short course of training at Quetta (Indian Army Command and Staff College at Quetta). The supply of trained staff officers from Home was naturally limited by non-availability and by the difficulties of transportation.

At the same time even before war broke out with Japan the work at Headquarters Malaya Command was particularly heavy including as it did war plans and the preparation of a country for war in addition to the training and administration of a rapidly increasing garrison.

Local War Office

In addition the Command was responsible for placing orders to bring up to the approved scale the reserve of all supplies and stores, except as regards weapons and all munitions. In fact Headquarters Malaya Command combined the functions of a Local War Office and those of a Headquarters of a Field force.

Authority for the raising of new units and for all increases in establishment had to be obtained from the War Office. With the pressure of war-time business it will be appreciated that delays occurred some of which had serious consequences.

In 1941 sea voyages from the United Kingdom were taking 2-3 months, so that there was a long delay in filling staff vacancies from Home, even after approval had been given. In consequence the strength of Headquarters Malaya Command was usually much below establishment.

Resources strained

When war with Japan broke out there were less than 70 officers at Headquarters Malaya Command, including the Headquarters of the Services. This is about the war-time establishment of the Headquarters of a Corps. Our resources were thus strained to the limit.

It should be realized that the G.O.C. Malaya did not have a free hand in developing the defences of Malaya. In principle, the defences were developed in accordance with a War Office plan which was modified from time to time in accordance with recommendations made by the G.O.C. By the beginning of 1941 the overall estimated cost of the War Office scheme had amounted to slightly over one? million, and actual expenditure to March 31, 1941, was over £4 million.

Although originally the defence items were mainly in respect of coastal artillery and fixed defences the scheme was later expanded to included services on landward defences. Such expansions of the main scheme had to receive War Office and Treasury approval and though they were submitted as major services, this entailed delay.

On December 11, 1941 when Malaya became an active theatre of operations, the War Office gave the G.O.C. Malaya a free hand with regard to such expenditure. In circumstances such as those which existed after the outbreak of World War 11 it is recommended that very much wider powers should be delegated to General Officers Commanding in important potential theatres who would naturally act in consultation with their Financial Advisers.

It cannot be too strongly stressed that the object of the defence was the protection of the Naval Base, and later of the Air Bases also at Singapore.

First Defence Plans

When in 1921 it was decided to build a Naval Base at Singapore, it was considered that the security of that base depended ultimately on the ability of the British Fleet to control sea communications in the approaches to Singapore. This it would doubtless have been able to do as soon as it had been concentrated in the Far East. For success, therefore, the Japanese would have had to depend on a “coup-de-main” attack direct on to the island of Singapore.

At that time the range of military aircraft was limited and it was considered that the only area suitable for the operation of shore-based aircraft against Singapore was a strip of land in the vicinity of Mersing on the East coast of Johore. Further the long sea voyage from Japanese territory would both have limited the size of the expedition and greatly prejudiced the chances of obtaining surprise. It was against this type of attack that the defences were initially laid out. The problem was one mainly of the defence of Singapore Island and the adjoining waters. For this a comparatively small garrison only was required.

Influence of Air

The rapid development of Air Power greatly affected the problem of defence. Singapore became exposed to attack by carrier-borne and shore-based aircraft operating from much greater distances than had previously been considered possible.

Similarly our own defence aircraft were able to reconnoitre and strike at the enemy at a much greater distance from our own shores. In April 1933, as a result of Japan’s withdrawal from the League of Nations, the Cabinet decided that immediate steps should be taken to increase the defences of Singapore. As a result of these decisions the question with location of aerodromes arose. In order to obtain the greatest possible value from the range of aircraft, it was urged that new aerodromes should be constructed on the east coast, an area which it had up till then been the policy to leave as undeveloped as possible, consistent with civil requirements, so as to present the enemy with difficult transportation problems should he land on that coast. It was obvious from the start that these aerodromes, if constructed on the east coast, would present the Army with fresh commitments for their defences – commitments which the existing garrison would be quite unable to meet. When war with Japan broke out, three aerodromes had been constructed in the State of Kalantan and a further one at Kuantan and a landing ground at Kahang in Eastern Johore.

Seventy Days’ Plan

Although these were strategically well placed for air operations, they were quite inadequately defended either by land or air forces. In 1937 the defence policy was still based on the fundamental assumption that the British fleet would sail from Home waters immediately on the outbreak of war with Japan and would arrive at Singapore within a maximum of 70 days. It was further assumed that the arrival of the fleet in the Far East would automatically put an end to any danger of capture of Singapore. It followed from these assumptions that the defence plan only had to provide against such types of operations as the Japanese might hope to complete successfully within 70 days and that the role of the garrison was confined to holding out for that period.

|

Percival’s Foresight In November 1937, having as G.S.O.1., Malaya, made a careful study of the problem of the defence of Singapore, I prepared on the instructions of the General Officer Commanding (Major – General, now Lieut. – General Sir W,G. S. Dobbie) an appreciation and plan for an attack on that place from the point of view of the Japanese. |

North Attack Fears

In May 1928, General Dobbie in another appreciation of the defence problem wrote:

“It is an attack from the northward that I regard as the greatest potential danger to the fortress. Such an attack could be carried out during the period of the north-east monsoon. The jungle is not in most places impassable for infantry.”

Up to the summer of 1939 the defence policy continued to be based on the assumption that the British Fleet would sail from Home waters immediately on the outbreak of war with Japan whatever the situation in Europe might be. It was then, however, officially recognised that this might not be possible.

180 Days’ Plan

The “Period before Relief” was increased from 70 to 180 days and authority given for reserves to be built up on that scale.

In August, 1939, the 12th Indian Infantry Brigade Group, which had been held in readiness for this purpose, was, in view of the threatening political situation, despatched from India to Malaya.

In 1940 the problem, which had hitherto remained one of the defence of Singapore Island and of a portion of Johore, developed and had appeared inevitable as early as 1937, into one of the defence of the whole of Malaya

The G.O.C. asked for official confirmation of this. The problem was further complicated by the collapse of France in June 1940, the immediate result of which was that Malaya was exposed to a greatly increased scale of attack. The necessity for holding the whole of Malaya, with reliance primarily on Air Power, was recognised.

In September, 1940 the Japanese occupied the northern portion of Indo-China, thereby greatly increasing the threat to Singapore. In fact, the whole conception of the defence problem had been changed because a Japanese invading force, instead of having to be transported all the way from Japan could now be concentrated and prepared within close striking distance of Malaya.

Forces Wanted

The Singapore Defence Conference held in October 1940 attended by representatives of Australia, New Zealand, India and Burma, and by one American observer estimated that 566 1st Line aircraft would now be required and that, when this target was reached, the strength of the land forces should be 26 battalions with supporting arms, ancillary services, etc.

The Army estimate was accepted by the Chiefs of Staff who, however, declined to increase the previously approved air scale. The general situation and war plans were further discussed at staff conversations with officers from the Dutch East Indies on 25-29th November, 1940, at a conference with Dutch and Australian representatives and United States observers in February 1941. (“A.D.A. Conference”) and at a full conference with American and Dutch (as well as dominion) representatives in April, 1941 (“A.D.B. Conference”).

Reinforcements

Further reinforcements now began to arrive in Malaya. In August 1940, two British battalions arrived from Shanghai on the evacuation of the latter place, and in October and November, 1940, the 6 and 8 Indian infantry Brigades, both of the 11 Indian Division (Major-General Murray Lyon) reached Malaya. In February 1941, the first contingent of the Australian Imperial force (A.I.F.) arrived.

|

It consisted of the headquarters and Services of the 8 Australian Division (Lieutenant-General Gordon Bennett) with the 22 Australian Infantry Brigade Group. In March 1941, the 15 Indian Infantry Brigade and the 1st Echelon of the 9 Indian Division (Major-General Barstow) arrived from India and one Field Regiment from the U.K., followed in April by the 22 Indian Infantry Brigade also of the 9 Indian Division. |

In May the 1st Echelon of headquarters 3 Indian Corps (Lt-General Sir Lewis Heath) arrived, and was located at Kuala Lumpur. It took over the 9 and 11 Indian divisions, the Penang fortress and the Federated Malay States. Volunteers (FMSVF). Some readjustment of formations in the two Indian Divisions had previously been made.

“Matador”

Before leaving London to take command in May, 1941, I discussed on broad lines a proposal which was then under consideration to advance into south Thailand if a favourable opportunity presented itself. Immediately after taking over command I was instructed by the C-in-C Far East to give this matter my further detailed consideration. It was also discussed on several occasions at conferences. The operation was known as MATADOR.

I was informed that it could not be carried out without reference to London, since MATADOR could only be put into effect if and when it became clear beyond all reasonable doubt that an enemy expedition was approaching the shores of Thailand. As time would then be the essence of the problem it appeared almost certain that by the time permission had been asked for and obtained, the favourable opportunity would have passed.

The military advantages of the occupation of South Thailand, or of part of it, were great. It would enable us to meet the enemy on the beaches instead of allowing him to land and establish himself unopposed. It would provide our Air force with additional aerodromes and, by denying these aerodromes to the enemy, it would make it far more difficult for his air force to interfere with our sea communications in the Malacca Straits.

Too Few Troops

It was a question, however, whether it was a sound operation with the meagre resources available. No troops could be spared for the operation other than the 11 Indian Division, strengthened by some administrative units.

The proposal to occupy the narrow neck of the Kra Isthmus was rejected as being too ambitious and the discussions centred round the occupation and denial to the enemy of the Port of Singora and the aerodromes at Singora and Patani. After careful examination of the problem, it was decided:

(a) That provided a favourable opportunity presented itself, the operation MATADOR would be put into effect during the period October-March

(b) That it would take the form of (i) an advance by road and rail to capture Singora and hold a defensive position north of Haad’yai Junction and (ii) an advance from Kroh to a defensive position, known as “The Ledge” position on the Kroh-Patani road some 35-40 miles on the Thailand side of the frontier. The reason for this limited objective on the Kroh front was lack of resources both operational and administrative.

(c) That at least 24 hours start was required before the anticipated time of a Japanese landing.

Money Printed

Detailed plans were worked out and preparations made for this operation. Maps were printed, money in Thai currency was made available and pamphlets for distribution to the Thais were drafted, though to preserve secrecy, the printing of them was deferred till the last minute.

By a special arrangement made by the C.-in-C. Far East, authority was obtained for a limited number of officers in plain clothes to carry out reconnaissance in South Thailand.

In all 30 officers including some of the most senior officers, were able to visit Thailand in this way. They frequently met Japanese officers who were presumably on a similar mission.

On December 5, 1941, I was informed by the C.-in-C. Far East that in accordance with the terms of a telegram just received from London, MATADOR could thenceforward be put into effect without reference to London

(a) if the C.-in-C. Far East had information that a Japanese expedition was advancing with the apparent intention of landing on the Kra Isthmus, or

(b) if the Japanese violated any other part of Thailand.

Landings Possible

Throughout the whole length of the east coast of Malaya there are numerous beaches very suitable for landing operations. For the greater part of the year, the sea is comparatively calm off this coast. The exception is the period of the north-east monsoon. It had, however, been determined as a result of a staff ride held in 1937, that even during this monsoon landings were possible, though it was thought they might be interfered with for two or three days at a time when the storms were at their height.

In consequence, it was thought that the enemy would be unlikely to choose the period December-February if he could avoid it. In view of the possibility of enemy landings on the east coast, detailed arrangements had been made with the civil authorities for the removal or destruction of all boats and other surface craft on this coast on receipt of specified code words.

Prior to the outbreak of World War 11, Air Defence in Malaya had been for all practical purposes, limited to the anti-aircraft defence of selected areas on Singapore Island, though plans had also been made for the defence of Penang.

With the extension of the defence problem, however, to embrace the whole of Malaya and the more imminent danger of active operations in the Far East, the plans for active air defence underwent rapid expansion, and passive air defence was organized.

A.A. Defences

When hostilities opened there were 60 Heavy Anti-Aircraft guns in the Singapore area out of the 104 which had been authorised. Outside Singapore Island, there were no guns available for the defence of cities on mainland such as Kuala Lumpur and Ipoh.

In 1940 the Air Defence was strengthened by the arrival of fighter aircraft. A proportion of these was always retained at the Singapore bases for defence of the important objectives in that area, the remainder being allotted to the northern area, which appeared to be the most vulnerable to attack.

With the arrival in Malaya in the summer of 1941 of Group Captain Rice, who had had much experience in connection with the Air Defence of Great Britain, the task of building up a co-ordinated Air Defence scheme for Malaya was energetically pushed forward.

As part of the Air Defence scheme an efficient Warning System was essential. An organization of civilian watchers had already been started. Efforts were now made to extend this organization and provide it with better equipment.

There were two main difficulties.

1. Firstly, there was the difficulty of finding suitable people in the less developed parts of Malaya to complete the chain of watchers.

2. Secondly, and more important still, was the paucity of communications.

The civil telephone system in Malaya consisted only of a few trunk lines, which followed the main arteries of communication, and local lines in the populated areas.

This was quite inadequate for a really efficient Warning System, as it was impossible to allot separate lines for this purpose. There were a few radar sets available, but efforts to supplement the system with wireless communication met with only partial success owning to the unreliability of wireless in the difficult climatic conditions of Malaya.

Nevertheless, in spite of these difficulties, an organization was built up which proved of great value during the subsequent operations, though it should be pointed out that it covered South Malaya and the Singapore area only and that there was no adequate Warning System for North Malaya.

On August 2, 1941, I gave my estimate of the Army strength required to defend Malaya in a telegram to the War Office. Summarised it asked for: -

48 Infantry Battalions

4 Indian Reconnaissance units

9 Field Artillery Regiments

4 Light Anti-Aircraft Regiments

2 Tank Regiments

3 Anti-Tank Regiments

2 Mountain Artillery Regiments

12 Field companies with the necessary administrative units

This was exclusive of the Volunteers, the infantry, anti-aircraft and tank units required for aerodrome defence and also of the Anti-Aircraft units required for the defence of localities including the Naval Base.

The main difference in the above estimate over those which had been submitted previously was that it made provision for a 3rd Corps Reserve in North Malaya of one complete division and certain Corps Troops units, for a complete division instead of two brigade groups in the Kelantan-Trengganu Pahang area, for two regular infantry battalions for Penang and for a brigade group instead of one battalion in Borneo.

This estimate was accepted by the Chiefs of Staff, but it was recognised that the target could not, in the existing circumstances, be fulfilled in the foreseeable future. A working target was subsequently approved by the War Office.

On August 15, 1941, the second contingent of the Australian Imperial Force (A.I.F.) arrived in Malaya. It consisted of the 27 Australian Infantry Brigade with attached troops.

No Experience

The Brigade Group had had the advantage of a period of training in Australia but had had no experience of bush warfare. It was accommodated temporarily on Singapore Island pending the completion of hutted accommodation in West Johore and Malacca. In September the 28 Indian Infantry Brigade disembarked at Port Swettenham. It was composed of three Ghurkha battalions which, like other Indian units, had lost a large proportion of their leaders and trained personnel under the expansion scheme. It joined the 3 Indian Corps and was accommodated in the Ipoh area, being earmarked for operations under 11 Indian Division.

In November-December, 1941 two field regiments and one anti-tank regiment arrived from the U.K. and one field regiment and one reconnaissance regiment (3 Cavalry) from India. These were all placed under orders of 3 Indian Corps. The artillery regiments consisted of excellent material but were lacking in experience and had had no training in bush warfare.

The Indian reconnaissance unit had only recently been mechanised and arrived without its armoured vehicles. It was so untrained that drivers had to be borrowed for some of the trucks which were issued to it. On arrival of the 2nd Contingent of the Australian Imperial Force (A.I.F.) I decided to make certain alterations in the Plan of Defence.

A.I.F. In Johore

I ordered the A.I.F. to take over responsibility for Johore and Malacca and brought into Command Reserve for operational purposes the 12 Indian Brigade Group, leaving it under the Commander Singapore Fortress for training and administration.

My reasons for this step were: -

(a) I considered the dual task imposed upon the Commander Singapore Fortress of defending both Singapore Fortress and East Johore to be unsound as he might well be attacked simultaneously in both areas. Similarly some of the Fortress troops had alternative roles in the two areas.

(b) I was anxious to give the 22 Australian Brigade Group, which had now had six months’ training in Malaya, a role which involved responsibility.

(c) There was a greater probability under the new arrangement that the A.I.F. would be able to operate as a formation under its own commanders instead of being split up. The advantages of this need no explanation.

In this connection I had enquired on taking over command whether there were any special instructions with regard to the status and the handling of the A.I.F. I had been informed that there were none.

The responsibility of the defence of Johore and Malacca passed to the Commander A.I.F. at noon on August 29, 1941.

Excess Of Secrecy

In the summer of 1941, a Branch of the Ministry of Economic Warfare was started in Singapore. It suffered from an excess of secrecy and from a lack of knowledge on the part of the gentlemen responsible as to how to set about the work.

Thus valuable time was lost. Later, however, some very useful work was done by this organization. Apart from the garrison of Singapore Fortress and the Command Reserve, of which most units had been in Malaya for some time, there were in 1941 very few trained units in Malaya.

Few had more than two or three senior officers with experience of handling Indian troops and of the junior officers only a proportion had had Indian experience. The majority of the troops were young and inexperienced. The Australian units were composed of excellent material but suffered from a lack of leaders with knowledge of modern warfare.

The same applied in some degree to the British units in which there were few men with previous war experience. No units had had any training in bush warfare before reaching Malaya. Several of the units had in fact been specially trained for desert warfare.

Inexperience

To summarize the troops in North Malaya were less well trained when war broke out than those in the South. Had we been allowed a few more months for training, there is reason to suppose that great progress would have been made.

Throughout the Army there was a serious lack of experienced leaders, the effect of which was accentuated by the inexperience of the troops. For intelligence within Malaya the Services were naturally dependent to a great extent on the civil Police Intelligence Branch.

The Inspector General of Police was Chairman of the Defence Security Committee, of which representatives of the services and of the Civil Police were members. This Committee examined and made recommendations upon all matters affecting security in Malaya in whatever form.

The constitutional organization of Malaya necessitated multiple separate Police Forces and Police Intelligence Services, but the Inspector General of Police Straits Settlements was also Civil Security Officer for the whole of Malaya. Shortly before the outbreak of war the Malayan Security Service was set up to coordinate the work of the various Police organizations in the Peninsula, to establish a central control and uniform legislation for aliens to provide security control of the northern border and pan-Malayan direction from a central office in all police civil security affairs, which covered a very wide field.

In Infancy

Malayan Security was in its infancy but showed promising results and did much to overcome the difficulties inherent in the excessively complicated lay-out of the Peninsula. It must be recorded that Headquarters Malaya Command was not well supplied with information either as to the intentions of the Japanese or as to the efficiency of their Fighting Services.

At a Senior Military Commanders’ Conference held at my Headquarters as late as the end of October, 1941, to survey the defence arrangements and to consider the Far East situation as it affected Malaya at that time, a representative of the Far East Combined bureau painted a very indecisive picture of the Japanese intentions.

Early Warnings

Flights of Japanese aircraft over Malayan territory, orders to their nationals to leave Malaya and other indications, however, gave us sufficient warning of the coming attack.

As regards the Japanese Fighting services, it was known that their troops were intrepid fighters and that they were experts in Combined Operations, but their efficiency in night operations, their ability to overcome difficulties, and the efficiency of their Air Force had all been underestimated.

Information of Thailand’s attitude was similarly lacking, even up to within a few days of war. It is difficult to say whether the Thai officers who came on official visits to Malaya were sent with the intention of misleading us or not, but there can be no doubt that there was at least an advanced degree of co-operation between some of their most responsible authorities in Thailand and the Japanese, and that the preparations made in South Thailand by the Japanese for their landing there and for their attack on Malaya were made with the connivance, if not with the actual assistance, of those Thai authorities.

Early in 1941 the scale of armament had been dangerously low. In particular all Indian formations and units arrived in Malaya with a very low scale of weapons. After March, however, a steady and increasing flow came in Malaya, but it was not until November that formations received the higher scale of weapons and were issued with 25-pounder guns for the artillery.

Even then many units, i.e. Artillery, Signals, R.A.S.C. (Royal Army Service Corps) were below establishment in light automatics and rifles and there were never more than a few of these weapons in reserve.

Food Problem

The food problem was complicated with the Australian ration differing from the British ration and with the Indian and other Asiatic troops having their own specialised rations. Nevertheless, approximately 180 days reserve stocks of all types had been accumulated before hostilities broke out. The food supply for the civil population of Malaya was a complicated problem.

The question of a rationing scheme had been under consideration by the Civil Government for some years but by summer of 1941 no result had been achieved. Committees appointed to examine the problem reported that the difficulties in producing a rationing scheme for the Asiatic population were so great that they could not put forward a satisfactory solution.

As a result when hostilities broke out, only a modified and limited scheme existed. In the light of a subsequent experience it appears that it should have been possible to produce a workable scheme, though it is true that during the campaign there was no shortage of foodstuffs for the civil population.

The hospital accommodation which had been prepared in peace-time was of course quite inadequate for the increased garrison. However, the Civil Medical Services were well developed.

The Civil Population

The European civilians in Malaya fell into two main categories, the Officials and the Unofficials. Most of them were men of energy and ability but there were some who, after many prosperous years in Malaya, especially during and after World War 1, had lapsed into an easier routine. To this the climate partly contributed.

This class was gradually disappearing, their place at the beginning of World War 11 being taken by a splendid type of young man who came out to join the Civil Service or to take up other appointments in civil life.

The picture, so often portrayed, of the “whisky-swilling” planter, was a gross misrepresentation of the conditions under which Europeans in Malaya lived at the time of World War 11. That the consumption of alcoholic liquor was fairly high is not to be denied, any more than it can be denied in other tropical countries, there was little drunkenness and the vast majority of Europeans lived very normal lives.

The standard of living, however, as a result of the natural wealth of the country and of the climate conditions, was exceptionally high – possibly too high for the maintenance of a virile European population.

I felt that in some quarters long years of freedom from strife had bred a feeling of security. This frame of mind was voiced in one of the local newspapers which wrote, when the decision to defend Penang was first announced: “There are not a few who view with concern the disturbance of the restful and placid atmosphere of Penang which will result from the military invasion.”

Even in 1941 there were those who found it difficult to believe that an attack on Malaya was within the bounds of practical politics.

Rubber and Tin

It should be stated, however that most of the unofficial Europeans were engaged, directly or indirectly in the rubber and tin industries which, by order of the Home Government, were working at maximum pressure. Bearing this fact in mind, Malaya, taken as a whole, shouldered its responsibility as war approached in the same loyal spirit as was evident elsewhere in the Commonwealth.

The bulk of the Asiatic population consisted of Malays and Chinese in approximately equal proportions. In general, the Chinese were to be found in the towns and larger villages while the Malays inhabited the country districts and the sea-boards. The reason for this was that the Chinese, being more industrious by nature and more commercially minded, had gained control of a great deal of the business of the country while the Malays, a more easy going and less ambitious race, were content to live on the natural products of the soil.

Chinese Divided

The Chinese themselves were of two categories – those who were and those who were not British subjects. For practical purposes the political sympathies of the Chinese population could be divided into four groups: -

(a) The pro-Kuomintang. This was probably the most powerful group.

(b) The pro-Wang Chingwei, i.e., those who were in sympathy with Japanese aims. A small and not dangerous group.

(c) The pro-Communists, predominately Chinese of the working classes. The most active and vocal group.

(d) The pro-British and Independents, the former being genuinely loyal adherents of the British Empire, and the latter those who wished to be left alone in the pursuit of fortune and their own self-interest. This group formed the large majority but unfortunately was only too prone to dragooning by (a) and (c) above.

The temporary reconciliation between the Kuomintang and the Chinese Communist Party following the invasion of Russia by Germany resulted in the formation in Malaya of a “United Front” which on the outbreak of war with Japan, absorbed all Chinese with the exception of Group (b).

As will by readily understood from the above summary, the Chinese population taken as a whole lacked homogeneity and centralised leadership.

The Malays

The Malays were divided into four classes, i.e., the Ruling class of Malay Nobles, the “Intelligentsia”, the artisan and clerical class, and the peasant. The Ruling Classes naturally felt that there should be an ever-widening control by the Sultans. Among the “Intelligentsia” were signs of a movement towards Nationalism. The other two classes were not in the broad sense politically minded.

The remainder of the Asiatic population totalling less than 20 percent of the whole consisted of Indians, Eurasians, Japanese, etc. The Indians, the great majority of whom were Hindu by religion with an active proportion of Sikhs were divided politically into: -

(a) Indian Nationalists who, through the Central Indian Association of Malaya, were bidding for control of the Indian population of the country on a strongly nationalist basis.

(b) The general mass of Indians, normally a peaceful but ignorant section of the population which was mainly interested in the quiet pursuit of its livelihood but was becoming an easy prey to the agitator.

(c) Indians who were whole heartedly British in their loyalty.

The Eurasians

The Eurasians were to be found mainly in the Colony and particularly in Singapore. The community as a whole was loyal and presented no political problem. It was not politically active. There were a number of Japanese in Malaya and, as all foreigners were treated alike, no special restrictions had up to 1941 been imposed on their activities. They were located mainly –

(a) In Singapore City, where there were large business houses, stores, hairdressing and photographic establishments, etc.

(b) In Johore, where they owned rubber and other estates and iron ore mines

(c) In Trengganu and Kelantan where they owned large iron ore mines.

(d) In Penang where they carried on similar activities to those in Singapore.

To sum up, the majority of the Asiatic population were enjoying the benefits which British occupation had brought to Malaya. They had so long been immune from danger that, even when that danger threatened, they found difficulty in appreciating its reality and in bringing themselves to believe that the even tenor of their lives might in fact be disturbed.

As will be appreciated from this brief review of the civil population of Malaya, the sense of citizenship was not strong nor, when it came to the test, was the feeling that this was a war for home and country.

Perhaps more might have been done by the Government in pre-war days to develop a sense of responsibility for service to the State in return for the benefits received from membership of the British Empire.

Malaya’s Charter

Prior to the outbreak of war with Japan Malaya had been given a charter for its participation in World War 11. It was to produce the greatest possible quantities of rubber and tin for the use of the Allies. This was a factor which had considerable influence on its preparations for war.

The subject of the proper utilisation of the available manpower had been carefully examined in peace-time. There was no leisured or retired class in Malaya which could be called upon for wartime expansion.

Soon after the outbreak of World War 11 the Governor and High commissioner, under the powers conferred upon him, ordered that all European males resident in Malaya should between certain ages be liable for service in one of the local volunteer corps.

At Singapore a Controller of Man-Power was appointed in place of the Man-Power Sub-Committee and in each Colony and State Man-Power Boards, on which both civil and military interests were represented, were set up to consider and give decisions on claims for exemption. Many exemptions had to be granted, even after allowing for the fact that in many cases Government and business could be carried on temporarily with reduced staffs. No liability to military service was imposed upon the Asiatic population.

Many of the Asiatics were of a type unsuitable for training as Soldiers and the difficulties of nationality, of registration and of selection would have been great. Moreover, as already stated, there were no rifles or other arms available with which to equip Asiatic units.

There was, however, great difficulty in filling the Chinese sub-units in the existing Volunteer organisation. This was in no way due to lack of available material or to lack of effort on the part of the military authorities. It was due chiefly to the lack of unity and of forceful leadership which existed among the Chinese population.

Volunteer Call-Up

Early in 1941, half the Volunteers were for the first time called out for a period of two months continuous training. It was unfortunate that in April-May labour troubles, involving the calling out of troops, developed on some of the estates in the Selangor and Negri Sembilan area and at the Batu Arang coal mines. This was imputed in some quarters to the absence of European officials, who were away at the training camps. At the instance of Government the calling out of the remainder of the Volunteers was postponed to a later date. It never in fact took place.

In Singapore and other large cities Local Defence Corps were formed.

They were trained in the use of small arms, but their role was primarily to assist the Civil Police. They were not incorporated in the military organisation but came directly under the Civil Government.

Labour Problems

The question of the conscription of labour in time of war had been considered and, in accordance with the advice of those best acquainted with labou5r conditions in Malaya, rejected as unworkable. The question of the control of labour in time of war had, however, been the subject of frequent discussions and tentative schemes had been worked out.

Although the grave labour problems which developed after the outbreak of hostilities had admittedly not been fully foreseen, some of the trouble could in my opinion have been avoided had the problems of war-time control of civil labour been tackled more energetically in time of peace.

The Singapore Harbour Board and the Municipality independent bodies operating in co-operation with the Government and carrying out its policy had their own labour forces. A few blast walls to important buildings were built.

Only very few air-raid shelters were constructed for the civil population. As regards Singapore itself this was partly due to the difficulty of constructing underground shelters, and partly due to the advice of the civil medical authorities, who were of the opinion that to obstruct the circulation of air by building surface shelters in the streets might well lead to epidemics.

A number of slit trenches had been dug but these soon became waterlogged and bred mosquitoes. In Singapore, the general policy was to rely rather on dispersal to camps constructed outside the town area. Apart from members of the Fighting Services, gas masks were provided only for those persons, such as members of salvage squads, whose duties might compel them to work in gassed areas.

This decision was made by the War committee after consultation with gas experts, on the grounds that the danger from gas bombing was not great in the climatic conditions of Malaya. Generally speaking it may be said that the arrangements for Passive Air Defence were in 1941 on too small a scale and inadequate to deal with anything but sporadic air raids.

Unreal atmosphere

The civil population following the example set by the Governor and High Commissioner were generous in their hospitality to the troops. Clubs were built, equipped and operated by civilians for their benefit. Many civilians invited troops to their houses and entertained them in other ways.

A debt of gratitude specially is due to the women of Malaya, many of whom worked untiringly in that enervating climate in the interests of the troops. Nevertheless, an atmosphere of unreality hung over Malaya. In the restaurants, clubs and places of entertainment peace-time conditions prevailed. There was no restriction on the consumption of food stuffs.

A measure to restrict the hours during which intoxicating liquor could be sold was not passed into law after long delays until November, 1941. Long immunity from war had made it difficult to face realities. Throughout the summer and autumn of 1941 the co-operation between the Services was good.

Relations with the Civil Government also showed a marked improvement. Generally speaking, officials throughout the country co-operated willingly with the military commanders.

No Team Spirit

I feel bound to record, however, that in my experience of Malaya there was a lack of the team spirit between the Service Departments on the one side and the Civil Government on the other in tackling problems of common interest. The vital importance of attaining the common object, i.e., the security of Malaya, was at times overshadowed by local interests, aggravated by the insistence of the Home Government on the maximum production of tin and rubber.

The task of balancing the requirements of a country of vital strategical importance to the Empire with those of a wealthy and prosperous commercial community was a difficult one requiring great tact and patience. Clashes of interest naturally occurred, followed very often by long delays, due in part to the complicated form of government. Other delays, as has so often happened before in our history, resulted from discussions as to the relative financial responsibility of the Home and Malayan on matters of defence. There was also a difficulty in getting full and accurate information as to civil defence measures.

During 1941 the tension with Japan increased and there were various signs that she was prepared for hostilities in the Western Pacific. Towards the end of July she occupied the southern part of Indo-China, where she increased her concentrations. She also increased her political activities in Thailand.

The attitude of the Thais was uncertain. On two occasions Thai military officers paid official visits to Singapore, where they protested their friendship for Britain. One of them was actually there when war broke out.

On the other hand, there is no doubt that the Japanese were permitted to make preparations in advance for their occupation of South Thailand, for our officers, carrying out reconnaissance’s in that area, frequently met Japanese there and one of them, though too late, found large petrol dumps on the Patani aerodrome which had been made ready for the occupation.

In the autumn many Japanese nationals received orders from their Government to leave Malaya, and Japanese reconnaissance aircraft flew over Malaya and Sarawak.

As a result of these activities varying degrees of readiness were from time to time ordered by the Commander-in-Chief Far East.

On December 1, 1941, the 2nd Degree of Readiness was ordered and a State of Emergency was declared. On the same date the Volunteer forces were mobilized.

The Air Situation

The Air Officer commanding Far East, air vice-Marshal Pulford, on taking over command at Singapore on April 26, 1941, was faced with tremendous difficulties. The aircraft at his disposal were still very deficient in numbers and few of them were of modern types.

There were no special army co-operation aircraft in Malaya. There was a great shortage of spare parts, reserve aircraft, and reserve pilots. The Air Force in Malaya had been drained of trained personnel to supply shortages in the Middle East. Trained personnel were also withdrawn from the Australian squadrons to act as instructors in Australia.

When war broke out with Japan, the total of operationally serviceable aircraft in Malaya was as under:-

Hudson General Reconnaissance land-based 15.

Blenheim 1 Bombers 17

Blenheim IV Bombers 17 including 8 from Burma

Vildebeeste Torpedo-Bombers 27

Buffalo Fighters 43

Blenheim 1 Night Fighters 10

Swordfish (for co-operation with Fixed Defences) 4

Shark (for target-towing, reconnaissance (recce). and bombing) 5

Catalinas 3 (of which 1 in Indian Ocean)

Total 141

This contrasted with the 566 1st Line aircraft which had been asked her (sic). In addition, to the above, there were a few Light aircraft (Moths etc.,) manned by the Volunteer Air Force. This was the Air force with which we started the war.

There was in fact no really effective Air Striking force in Malaya and the fighters were incapable of giving effective support to such bombers as they were of taking their proper place in the defence. The A.O.C. was fully alive to the weakness of the force at his disposal. He frequently discussed this subject with me and I knew that he repeatedly represented the situation to higher authority.

When the war broke out with Japan on December 8 1941, there were some glaring weaknesses in the arrangements for the defence of Malaya. The Navy no longer controlled the sea approaches to Malaya and there was a great shortage of craft suitable for coastal defence.

There were no modern torpedo-bombers and no dive-bombers, the two types required for offensive action against an approaching seaborne expedition, and no transport aircraft, the type essentially required for the maintenance of forward troops in jungle warfare. In addition, there were comparatively few trained pilots and there was a great shortage of spare parts.

The dispersion of the land forces and the lack of reserves needs no stressing. The dispositions on the mainland had been designed primarily to afford protection to the aerodromes, most of which had been sited without proper regard to their security. The situation was aggravated by the fact that there was no adequate Air force to operate from them.

It is true that, even without this commitment, it would have been necessary, in order to protect the Naval Base, to hold at least most of Malaya but, had it not been for the aerodromes, better and more concentrated dispositions could have been adopted.

As soon as the threat to Malaya developed in the summer of 1940 everything possible was done, both at Home and in Malaya, to strengthen the land defences.

No Time

The fact that more could not be done was no doubt due to our Imperial commitments elsewhere. The time proved too short to put a country almost the size of England and Wales, in which there was no surplus labour, into a satisfactory state of defence. The financial control also had a restrictive effect.

As regards the Army itself, the troops generally were inexperienced and far too large a proportion of them were only partially trained. There was a shortage of experienced leaders, especially in the Indian and Australian units. Instead of the 48 infantry battalions and supporting arms (excluding the Volunteer Forces and troops required for aerodrome defence) which had been asked for, we had only 32 infantry battalions and supporting arms.

There were no tanks which as the operations developed, proved a very serious handicap. The Japanese did not gain either strategical or tactical surprise. Our forces were deployed and ready for the attack.

As regards Civil Defence, much had been done but, viewed as a whole, the preparations were on too small a scale. There were many who responded nobly as soon as the call came but it cannot be said that the people of Malaya were fully prepared for the part they were to play in a total war.

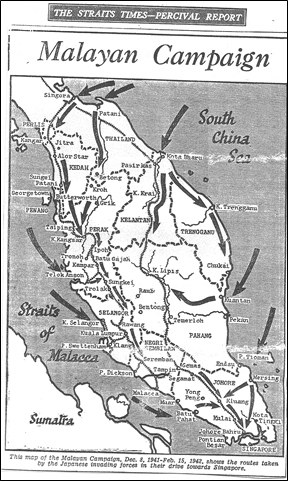

Jap Convoys

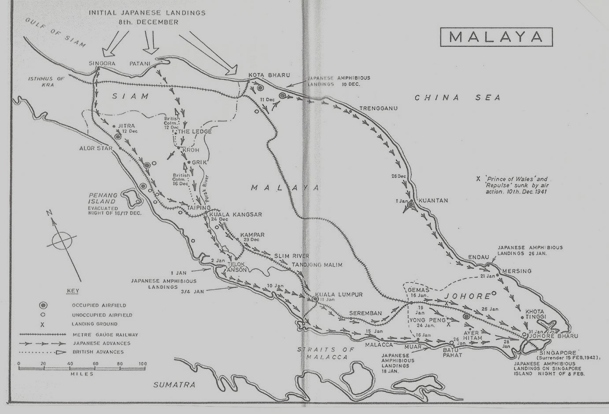

About 11:30a.m. on December 8, 1941, the morning air reconnaissance, which was watching the approaches to the Gulf of Thailand, reported having sighted Japanese convoys consisting of warships and transports approximately 150 miles S.E. of Pt. Camo (South Indo-China) steaming westward. Information that there were two separate convoys was received at 2.p.m.

The position of these convoys was about 80 miles E.S.E. of Pul Obi. At that time I was at Kuala Lumpur, whether I had gone by civil air line that morning to confer with the Commander 3 Indian Corps. I received the information by telephone about 3p.m. At 3.15 I ordered the commander 3 Indian Corps to assume the First Degree of Readiness, and anticipating that Operation MATADOR might be ordered, to instruct the Commander 11 Indian Division to be ready to move at short notice.

On returning to my headquarters at Singapore at 6:30p.m., I was informed that the C.-in-C. Far East appreciated that the Japanese convoy had probably turned North West with a view to demonstrating against and bringing pressure to bear on Thailand; that in consequence he had decided not as yet to order Operation MATADOR, also that one convoy consisted of twenty-two 10,000 ton ships escorted by one battle ship, five cruisers and seven destroyers, and the other of of twenty-one ships escorted by two cruisers and ten destroyers.

Two Hudson reconnaissance aircraft had been sent out at 4p.m. to shadow the convoys until relieved by a Catalina flying boat which would continue the shadowing throughout the night. These Hudsons failed to make contact owing to bad weather, which prohibited relief Hudsons being sent.

During the evening I called on the Governor and the C.-in-C. Far East to whom I reported that the First Degree of Readiness had been assumed by all troops under my command. The first Catalina sent out failed to make contact during the night December 6-7.

First Shots Fired

A second was despatched early on December 7 and instructed that, if no contact was established, a search was to be made from 10 miles off the west coast of Indo-China, as G.H.Q. anticipated that the convoys might be concentrating in the Koh Kong area where there was a suitable anchorage.

No reports were received from this Catalina and, from information subsequently received, it would appear that this boat was shot down by the Japanese. Further Hudson reconnaissances were sent but only single merchant vessels were sighted in the Gulf of Siam at 1:45p.m. and 3:45p.m. respectively.

These Hudsons were then sent on a diverging search off the Siamese Coast, and at 5:50p.m. one merchant vessel and one cruiser were sighted steaming 340 degrees. The cruiser opened fire on the reconnaissance aircraft. At 6:48p.m. under conditions of very bad visibility four Japanese vessels, perhaps destroyers, were seen off Singora steaming south.

For a period of nearly 30 hours after the first sighting the air reconnaissance sent out failed to make contact with the main invasion forces, owing to bad weather

If the report of the Catalina flying boat having been shot down by Japanese aircraft on the morning of December 7, 1941, is correct, then this was the first act of war in the Malaya area between Japan and the British Empire. If not, then the first act was the firing on the Hudson reconnaissance aircraft by the Japanese ship on the evening of December 7.

An appreciation of the situation showed that the enemy convoy, if it was bound for Singora, could reach there about midnight December 7-8, whereas if MATADOR was put into operation it was unlikely that our leading troops, even if they met with no opposition or obstacles on the way would arrive there before about 2a.m. An encounter battle with our small force and lack of reserves would have been very risky, especially as the enemy was expected to include tanks in his force.

“Matador” Cancelled

There was also the complication of part of our force having, owing to the lack of motor transport, to move forward by rail and subsequently be linked up with its transport in the forward area. For these reasons I informed the C.-in-C. Far East at a Conference held at Sime Road that I considered Operation MATADOR in the existing circumstances to be unsound.

On the Kelanian front about 11:45p.m. on December 7 the Beach Defence troops on Badang and Sabak beaches, the point of junction of which at the Kuala Paámat was about one and a half miles N.E. of the Kota Bharu aerodrome, reported ships anchoring off the coast.

Shortly afterwards our beach defence artillery opened fire and the enemy ships started shelling the beaches.

About 12:25a.m. December 8 the leading Japanese troops landed at the junction of the Badang and Sabak beaches and by 1a.m. after heavy fighting, had succeeded in capturing the adjacent pill-boxes manned by troops of the 3/17 Dogras.

The garrisons of the latter inflicted very heavy casualties on the enemy before being themselves wiped out almost to a man. Hudson aircraft between midnight and dawn pressed home numerous attacks in the face of heavy A.A. fire from warships and transports.

|

One of the transports which believed to have contained tanks and artillery was set on fire either by air attack or gunfire, or perhaps both, and prevented from discharging its cargo. As soon as the first landing took place the 2/12 Frontier Force Regt. (less one company West of the Kelantan River) and 73 Field Battery were ordered up from Chon-Dong with orders to prevent any penetration towards the aerodrome with a view to a subsequent counter attack. In the meantime I had informed C.-in-C. Far East and the Governor that hostilities had broken out. Singapore Raided |

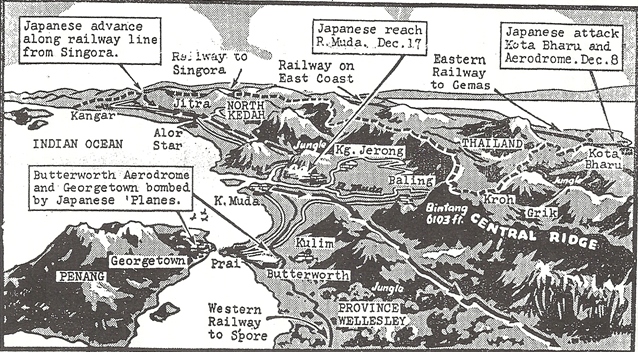

Jap Air Surprise

On return to the aerodromes in Kedah some of our aircraft were attacked by Japanese bombers and fighters while refuelling, and considerable losses were sustained. The aerodromes at Alor Star, Sungei Patanim Penang, Kota Bharu, Gong Kedah and Machang were all attacked on this day.

The performance of the Japanese aircraft of all types and the accuracy of their high level bombing had come as an unpleasant surprise. Our own air force had already been seriously weakened.

At 8:20a.m. G.H.Q. Far East reported that Operation MATADOR had been approved by the Chiefs of Staff if the Japanese attacked Kota Bharu but G.H.Q. added “Do not act.”

Air reconnaissance sent to Singora and Patani at dawn reported that enemy forces had landed at those places, that there were a number of ships lying off the coast and that the Singora aerodrome was in use. It was clearly too late now to put Operation MATADOR into effect, so I authorised the Commander 3 Indian Corps to start harassing activities and to lay demolition charges on the roads and railways.

At 10a.m. the Straits Settlements legislative council in accordance with previous arrangements met at Singapore. I took the opportunity to report the situation to it. At 11a.m. sanction to enter Thailand then having been obtained from the C.-in-C. Far East orders were issued to the Commander 3 Indian Corps to occupy the defensive positions on both the Singora and Kroh-Patani roads, and to send a mobile covering force across the frontier towards Singora to make contact and delay him.

On Wrong Foot

The change from an anticipated offensive, for which the 11 Indian Division had been energetically preparing for some weeks, to the defensive undoubtedly had a considerable psychological effect on the troops.

It was aggravated by the fact that on December 7 certain preparatory moves had been carried out within the division in preparation for MATADOR, including the moves of two battalions of the 15 Indian Infantry Brigade to Anak Bukit Station to entrain.

The division was thus caught to some extent on the wrong foot for the defensive operations which were to follow. It had, however always been realised that the chances of being able to put Operation MATADOR into effect were not great in view of the political restrictions and Commanders had been instructed to prepare for either alternative.

Possibly the defensive preparations had been to some extent sacrificed in favour of the offensive. It was originally intended that the column operating on the Kroh-Patani road, known as Krohcol and commanded by Lt. Colonel Moorhead, should consist of the 3/16 Punjab Regt., the 5/14 Punjab Regiment from Penang, one company sappers and miners, one Field Ambulance and a light battery of the Federated Malay States Voluntary Forces (F.M.S.V.F.).

The F.M.S.V.F battery had however, been unable to mobilise in time, and was replaced later by the 10 Mountain Battery from the North Kedah front.

The 5/14 Punjab Regt., was moved up to Kroh on December 8 leaving one company in Penang, but had not arrived when operations started. Responsibility for operations on the Kroh front was on December 8 delegated by Commander 3 Indian Corps to Commander 11 Indian Division.

At 10p.m. December 8 the Commander Krohcol received orders to occupy “The Ledge” position some 38-40 miles beyond the frontier. It was hoped that the Thais would at worst be passively neutral. These hopes were speedily disillusioned.

As the vanguard crossed the frontier at 3p.m. they were immediately engaged by a light automatic post manned by Thais. Throughout the afternoon the advance was disputed by snipers assisted by road blocks, the enemy fighting skilfully. By nightfall our troops had cleared only three miles of the road and then they halted for the night.

The enemy were all Thais, some of whom were armed with Japanese rifles.

North Kedah Front

On the North Kedah front, a mechanised column consisting of two companies and the carriers of the 1/8 Punjab Regt., with some anti-tank guns and engineers attached, crossed the frontier at 5:30p.m. December 8, and moved towards Singora to harass and delay the enemy. Concurrently an armoured train with a detachment of 2/16 Punjab Regt., and some engineers, advanced into Thailand from Padang Besar in Perlis.

The Singora column reached Bah Sadao 10 miles north of the frontier at dusk, where it halted and took up a position north of the village. Here about 9:30p.m. it made contact with a Japanese mechanised column, headed by tanks and moving in close formation with full headlights. The two leading tanks were knocked out by the anti-tank guns, but the Japanese infantry quickly debussed and started an enveloping movement.

Our column was then withdrawn through the outpost position at Kampong Imam, destroying two bridges and partially destroying a third on the way back. Meanwhile the armoured train party had reached Klong Gnea, in Thailand and successfully destroyed a large bridge before withdrawing to Padang Besar.

Kelantan Front

To return to the Kelantan front. As soon as it had become clear from the dawn reconnaissance that there were no ships off the coast further south, the Commander Kelantan force moved up his reserve battalion, the 1/13 Frontier Force Rifles, with some anti-tank guns attached from Peringai with a view to counter attacking the enemy who had landed.

Some local counter-attacks had already been put in and progress made. By 5p.m. the advance of our troops was stopped. About 4:30p.m. the R.A.F. Station Commander decided that Kota Bharu aerodrome was no longer fit to operate aircraft and obtained permission from the A.O.C. Far East to evacuate the aerodrome.

All serviceable aircraft were flown away and the ground staff was evacuated by road to rail-head. No offensive or reconnaissance aircraft were then available in that area.

By 7p.m. more ships were reported off the Sabang beach and the Japanese had started to infiltrate between the beach posts in the Kota Bharu area. The commander Kelantan force therefore decided to shorten his line and ordered a withdrawal during the night to a line east of Kota Bharu.

It was pouring with rain and pitch dark and communications had been reduced for the most part to Liaison officers. It was therefore not surprising that some of the orders went astray. As a result part of the 1/13 Frontier Force rifles were left behind.

Japs Gain Objectives

Thus within 24 hours of the start of the campaign the Japanese had gained their first major objective, but at considerable cost. It is believed that the forces landed in Kelantan consisted of rather less than one Japanese division. This force lost its accompanying tank formation and many of its guns before it got ashore and subsequent reports indicated that the Japanese suffered some of their heaviest losses during the first day’s fighting in Kelantan.

A midday air reconnaissance reported two cruisers and fifteen destroyers moving towards Besut, six transports lying off Patani and twenty-five transports off Singora.

The War Council

On December 10, 1941, in accordance with instructions received from the Home Government, the Far East War Council was formed at Singapore. Its composition was as under: -

Chairman

The Rt. Hon. A. Duff and High Commissioner, Malaya.

The Commander-in-Chief Far East.

The Commander-in-Chief Eastern Fleet.

The General Officer Commanding Malaya

The Air Officer Commanding Far East

Mr Bowden representing Australia, and later Sir George Sansom, as being responsible for propaganda and Press control.

Secretary

Major Robertson, the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders (staff officer to the Cabinet representative in the Far East). In addition to the above Lieutenant-General Gordon Lieutenant Commanding the A.I.F. was told that he was at liberty to attend meetings if and when he wished to do so, and that he would be informed if and when matters particularly affecting Australia were on the agenda.

In January, after the departure from Singapore of Mr Duff Cooper and Sir George Sansom, the Governor and High Commissioner became Chairman, Mr Scott took Sir George Sansom’s place and Mr Dawson became Secretary.

Later, Brigadier Simson, as Director General of Civil Defence, joined the Council.

Rain Interferes

The defences in the Jitra position, although well advanced, were not complete. In addition, most of the posts had become waterlogged after a week’s heavy rain, which still continued for the next few days. It was in these conditions that the troops set to work to complete the defences.

The rain also had a serious effect on the demolitions, all of which were charged on December 8, but several of which subsequently failed to operate. On the Singora road the advance of the enemy column was delayed by the engagement at Ban Sadao and by demolished bridges and it was not until 4:30a.m. December 10 that contact was again made about the frontier a few miles north of Changlun.

On December 10 the covering troops of 6 Brigade withdrew to Kodiang without incident, carrying out important demolitions on the railway before they went. This withdrawal entailed the evacuation of the State of Perlis, as a result of which Britain was accused by one of the Perlis Ministers of State of violating her treaty by abandoning the State.

About 8a.m. December 11 the 1/14 Punjab Regt was attacked in the Changlun position but succeeded in driving the enemy back. By midday, however, the enemy attacking from the right flank had penetrated into the middle of our position and Commander of the Covering Force decided to withdraw behind the Asun outpost position, calculating that he would be able to reach there before the enemy tanks could negotiate the damaged bridges. At 2:30p.m. however, he was ordered by the divisional commander to occupy a position 1 ½ miles north of Asun with a view to imposing further delay on the enemy.

Japanese Tanks

At 4:30p.m. when the force was moving back, covered by a rearguard, occurred the first of many incidents which showed the influence of the tank on the modern battlefield, especially against inexperienced troops. Suddenly, with little warning, 12 Japanese medium tanks followed by infantry in lorries and other light tanks attacked the rear of the column. Few of the troops had ever seen a tank before.

The tanks advanced through the column inflicting casualties and causing much confusion and approached the bridge in front of the Asun outpost position. The demolition exploder failed but the leading tank was knocked out by anti-tank fire and blocked the road. By 6:30p.m. the tanks followed by infantry, had come on again and broken into the outpost position held by the 2/1 Gurkha Rifles. Shortly afterwards the Battalion Commander decided to withdraw all his three companies. But communications had been broken and of the forward companies only 20 survivors ever rejoined. The losses of the battalion in this action were over 500.

On the Perlis road, as may often happen, with inexperienced troops a demolition was prematurely exploded behind the covering and outpost troops. For various reasons it was not repaired in time although there was no contact on this front, and all the transport, guns and carriers of the covering and outpost troops and seven anti-tank guns in the main Jitra position were lost.

Withdrawals are admitted to be among the most difficult operations of war even for seasoned troops and the above incidents which have been described in some detail, serve to illustrate the great difficulty of conducting them successfully with inexperienced troops. They had profound influence on the Battle of Jitra.

At the same time I am of the opinion that some of the trouble might have been avoided had the commanders reacted more swiftly to the problems created by the appearance of tanks on the battlefield.

The Kroh Front

The advance was continued early on December 9. Our column was still opposed by the detachment of the Thailand Armed constabulary which was now some 300 strong and which adopted guerrilla tactics. As the leading troops approached Betong, however, in the afternoon all opposition ceased.

At first light on December 10 Krohcol embussed in the 2/3 Australian Reserve Motor Transport Company (2/3 RMTC), and moved forward towards “The Ledge” position. When about four miles short of its objective the advanced guard came under fire from Japanese troops. It continued to advance rapidly for 1 ½ miles and then was held up. An encounter battle developed in which there was heavy fighting with considerable casualties on both sides, but again the issue was decided by Japanese tanks which made a surprise appearance on this front.

During the afternoon of December 11 the enemy made repeated attacks on the forward troops of Krohcol, but were repulsed with heavy losses. The battalion casualties, however, after three days and nights fighting had passed the 200 mark.

The Commander Krohcol estimated that he was opposed by four enemy battalions and reported accordingly to Headquarters 11 Indian Division. It was the night after the affair at Asun, recorded above and in reply, the Commander 11 Indian Division sent a personal message to the effect that the object of Krohcol must now be to ensure the safety of the whole division.

The Commander Krohcol was given full permission to withdraw as necessary to the Kroh position where his stand must be final. A detachment of anti-tank guns was sent to this front.

Kelantan Front

Civil plans during the first day of war had gone smoothly under the capable direction of Mr Kidd, the British Adviser. During December 8 all European women and children were withdrawn to Kuala Krai and thence out of the State, and plans for the denial of sea and river craft to the enemy were put into effect. The few Asiatic civilians who wished to leave did so under control and there was no refugee problem. During the night, December 8-9 heavy fighting went on at the Kota Bharu aerodrome.

Having in view the threat to his communications should the enemy make fresh landings further south on the coast of Kelantan, the Commander Kelantan force, decided on the morning of December 11 to give up the Gong Kedah and Machang aerodromes, which were no longer required by our air force, and to concentrate his force south of Machang to cover his communications.

Unfortunately the runways at both the Gong Kedah and Machang aerodromes had to be left intact, for at neither had the demolition arrangements been completed. Information was received that the Japanese had on December 10 landed another force at Besut in South Kelantan.

On December 9, Japanese aircraft attacked the Kuantan aerodrome. In the afternoon the aerodrome was abandoned as being unserviceable. Early on the night December 9-10 reports were received from the northern part of the beach defences that the enemy ships were approaching the beaches and about 4a.m. torpedo-bombers attacked three ships off this coast.

No landing took place but subsequently some boats with Japanese equipment were found on the beach south of Kuantan. This incident had a great influence on the movements of the “Prince of Wales” and “ Repulse.”

Naval Operations

In accordance with pre-war plans, submarines of the Royal Netherlands Navy operated off the east coast of Malaya and in the approaches to the Gulf of Thailand during this period. They reported sinking 4 Japanese transports off Patani on December 12, and a merchant ship and a laden oil tanker off Kota Bharu on December 12 and 13. Towards dark on December 8 Admiral Sir Tom Phillips put to sea with the battleship “Prince of Wales” and the battle cruiser “Repulse” to attack the Japanese ships in the Gulf of Thailand. They were escorted by four destroyers.

The decision to take the fleet to sea was made by the Commander-in-Chief Eastern Fleet, after discussing the situation with the Commander-in-chief, Far East.

On the evening of December 9, the British Fleet was sighted by a Japanese submarine and also by Japanese reconnaissance aircraft. The Japanese air striking forces, which were being held in readiness, probably in South Indo-China, for this purpose, set off for a night attack on the fleet but ran into thick weather and were forced to return to their base.

The Commander-in-Chief, Eastern Fleet, realising from his having sighted Japanese aircraft that his movements had been seen, and that the element of surprise had been lost, decided to abandon the project and return to Singapore.

Kuantan Trap

During the night December 9-10, however, he was informed by his shore headquarters at Singapore that a landing had been reported at Kuantan. Reconnaissance aircraft were flown off and the Fleet closed the shore in order to clear up the situation before returning to Singapore. Shortly after daylight the Fleet was again located by Japanese reconnaissance aircraft and their striking force was again despatched. About 11:15a.m. it attacked the “Prince of Wales” and “Repulse” when about 60 miles off Kuantan, and by 1:30p.m. both these ships had been sunk.

Fighter aircraft from Singapore were despatched as soon as the attack on the ships was reported but only arrived in time to see them go down. A total of 2,185 survivors were picked up by the destroyers and brought to Singapore.

The Commander-in-chief, Eastern Fleet, was lost and was succeeded by Vice-Admiral Sir Geoffrey Layton. With the sinking of these two ships the Japanese again obtained undisputed control of the sea communications east of Malaya and became exposed to attack.

I wish to pay tribute to the gallant manner in which the C.-in-C. Eastern Fleet endeavoured to assist the land and air forces by attacking the enemy’s sea communications.

Air Operations

Early on December 9 our Air force attacked targets in the Singora area. Owing to lack of fighter support five out of 11 of our aircraft were lost. During the morning Alor Star aerodrome was again heavily bombed and was evacuated later in the day, the buildings being set on fire.

Further attacks were carried out on Sungei Patani and Butterworth aerodromes and again owing to the lack of light anti-aircraft and fighter defence, casualties were inflicted on the aircraft grounded there.

On December 10 our aerodromes on the Kedah front were again heavily attacked. Sungei Patani aerodrome was evacuated during the day.

Penang Raids

On this day also the first of a series of heavy Japanese air attacks on Penang Island took place. It was carried out by 70 enemy bombers and Georgetown was the target. There were no anti-aircraft defences, except small arms fire and few shelters.

The inhabitants thronged the streets to watch the attack. The casualties from this raid ran into thousands. A large part of the population left Georgetown and moved to the hills in the centre of the Island but the A.R.P. and the Medical and the Nursing Services stood firm.

The small garrison in addition to manning the defences was called upon to assist the Civil Administration by taking the place of labourers and of the personnel of essential municipal services. It also had to assist in burying the dead.